In January 1991 Dale Perryman arrived in Ruidoso, New Mexico, for a weekend ski trip. He ate an egg burrito, drank a Gatorade, then rode the ski lift up the mountain with a friend to hit the runs. It turned out to be his last meal for days.

Unaware that a blizzard was gathering on the mountain, the friends became separated in a whiteout.

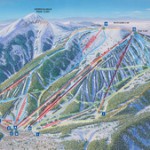

Dale attempted to navigate back down the mountain but he unknowingly skied over a fence buried in the snow, one which separated the regular ski areas from the closed side of the mountain, and this placed him in the one area rescuers would never look.

At first Dale tried to ski his way out but he was disoriented in the snowfall and low visibility.

He had no food, and his clothes became soaked from a spill into a stream as he trudged through thigh-high snow. He had to stop to massage his wet feet every hour or so in order to keep frostbite from setting in.

“Every hour I would lose feeling in my feet. I would put my socks under my armpit to warm them and then place them on my feet and massage my toes. You soon realize it’s not a game.”

A search and rescue operation had begun scrambling on the mountain, but the searchers were looking in the wrong place: the evacuated ski runs. So Dale spent the frigid below-zero evening making a berth in a snowbank and lining it with pine needles, instinctive survival tactics. He tried to stay awake, knowing that he would very likely freeze to death if he nodded off.

The next day he wandered alone in the snow, shouting into the empty trees and trying to keep himself warm, which became a constant, unending task. He spent that day and the next without food or sleep, and the search for Dale – which had by then mobilized teams of people – was about to be called off. The Associated Press had picked up the story and reported that rescuers gave the missing skier a dwindling 2% chance of being found alive after 3 days of exposure on the mountain. Hallucinating, ravenous, suffering from lack of sleep, hypothermia and dehydration, Dale shouted to the helicopters he saw circling but wasn’t seen because his green ski jacket looked like a tree from the air.

But he kept shouting and it eventually saved his life.

Miraculously Dale was rescued by a man on the search team who heard the shouts and later said he’d been given a divine vision exactly where Dale was on the mountain – on the closed side where no one expected him to be. This rescuer, coincidentally also named Dale [Webb] of the White Mountain Search and Rescue team, had shaken off pleas from others that the weather was still too dangerous and went up the mountain alone at great risk…to find the other Dale, who was at this point approaching death. Dale Webb’s quote when he found Dale was, “I had been praying this morning & God told me where you were at”.

Dale Perryman was found, helicoptered off the mountain, and taken to a local hospital.

Doctors and rescuers were astonished at his relatively sound physical condition, and surprised at the correct survival tactics he’d employed without any previous survival training. He didn’t even have frostbite. Dale will tell you that at times during his travails, he had a sense that someone was somehow there with him “brainstorming,” helping him come up with ideas to survive.

If you are interested in seeing some real newspaper articles from this experience click here.

What feelings did you go through during that time?

DP: Well the first feeling is embarrassment, believe it or not. Then my brain kicked in with one purpose…survival. Like, urinating an arrow in the

snow in the direction I was moving. At first I was too proud to yell

help, but then things get worse and all pride is gone. You’re yelling help with

every ounce of energy, yelling for an extra ounce of energy just to take one more step.

I have a soft spot in my heart for anybody going through a survival

experience because I’ve been there. I’ve felt what they felt. I know how

those missing miners in Pennsylvania felt recently. A few tears sometimes come as I recall those feelings.

What did the experience teach you about helping others?

DP: I wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for volunteers. Dale Webb, I salute you. And I want to give back to volunteers as a result of what one volunteer rescuer did for me.

How did the mountain experience most affect you?

DP: Well, it serves as a reference point. Afterward I realized that there were many things that we worry about that in the big scheme of things, just aren’t that big of a deal. During those 54 hours, the pine tar on my ski jacket was no big deal, the length of time it took to taxi in from the airplane runway….was no big deal. Getting a close parking place was no big deal. Lots of things we worry about are not really the important things.

It also showed me that God chooses to intervene at times in our lives. There were too many things that happened to believe that they were all a coincidence. God heard the prayers of so many that day and chose to intervene in a way that encouraged the beliefs of those who were praying for my survival.

So what are the important things?

DP: Moments. Laughing, living, loving, doing what you love, leaving a legacy. These are the things that matter. I try to incorporate these lessons in my training whenever possible. It’s really about the journey, not the destination.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Youtube

Youtube GooglePlus

GooglePlus LinkedIn

LinkedIn